Coalesce to Write New Chapter in History of Bay Area Bass

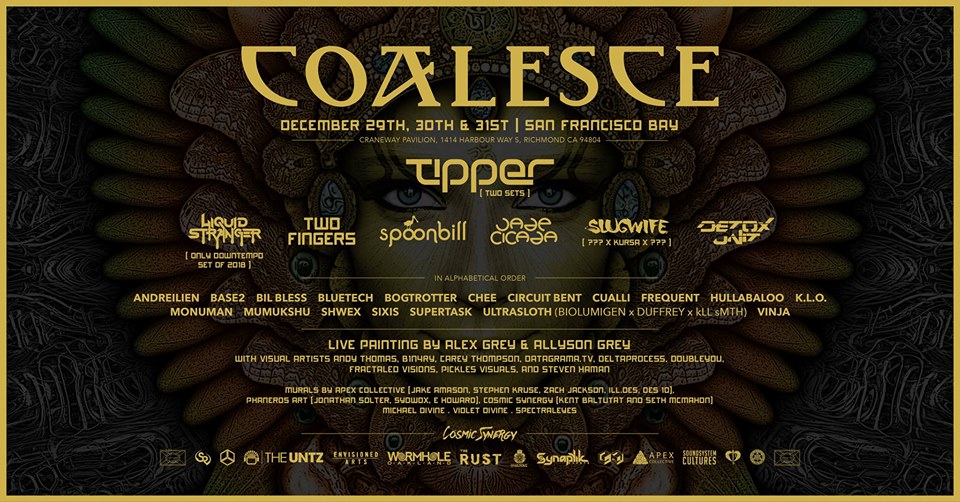

To ring in a new year with the best of intentions, Denver-based promoter Cosmic Synergy is organizing one of the most prolific and far-reaching gatherings of glitch music and psychedelic culture seen in this generation; Coalesce. They’ve commissioned the foremost electronic producers and visionary visual artists of generations past and present to transform the Craneway Pavilion in Richmond, CA, a hulking former factory jutting into the San Francisco Bay, into a vibrational intersection on December 29-31 as the calendar turns once again.

From the Summer of Love in the Haight-Ashbury to the first Burning Man on Baker Beach beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, psychedelia and explorative consciousness are part of the bedrock of the Bay Area. When rave culture first came to the United States, it found the most fertile ground in the Bay. By selecting this site, Coalesce ambitiously joins a storied history of music and mind expansion. It’s said that history repeats itself. Indeed, much of the music booked for Coalesce first rose to prominence in San Francisco clubs, Santa Cruz beaches, or the Black Rock City playa father to the east.

Recently, though, factors from gentrification and legalization to disuse and disaster have led the psychedelic electronic music scene to decline in the region that was once its mecca. Coalesce arrives then into a space that while not dead, is in many ways dormant. At most, the ambitious scope of Coalesce may help rekindle a cultural flame, and at least will provide dramatic context for attendees to help write a new chapter in the history of counterculture.

When charged up youths first came to San Francisco in the mid 1960s pressing for cultural shift, music was an adhesive that bound together their collective dreams and gave expression to their hopes; psychedelic rock, folk, blues, Americana. But also embedded in this familiar flower scene were seeds that would later sprout into an electronic spring.

Founded in 1961, the San Francisco Tape Music Center attracted composers that experimented with primordial synthesizers and began manipulating tapes to musical effect through looping and splicing. Existing synthesizers could create but a few sounds, and couldn’t modulate or alter the sounds at all. With a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Center commissioned one Don Buchla to build a new sort of synthesizer. Buchla created one of the first modular electronic music systems from components that could each generate then modify a “musical event” (a sound). Today, popular eurorack synthesizer modules are influenced by this Buchla format. These modules are synonymous with modular “west coast” synthesis.

Ramon Sender, Mike Callahan, Morton Subotnick, and Pauline Oliveros, the founders of the San Francisco Tape Music Center. (Credit: Art Fisch)

Associates of the Tape Music Center also began experimenting with music itself, people like the landmark minimalist Terry Riley, whose work “In C” created a powerful ripple in thought patterns and music circles in 1968. Riley inverted compositional norms by writing a classical piece for an indefinite number of performers to be performed for an undefined amount of time. As a result, “In C” offered a transcendent musical experience that dissolved boundaries of time and space for its audiences.

In 1966, the Trips Festival at the Longshoreman’s Hall in San Francisco coalesced bands, theater performers, dancers, vagabonds, wharf rats and film producers for an event billed as “the FIRST gathering of its kind anywhere - a new medium of communication & entertainment.” Signaling the start of the short-lived but broadly impactful “hippy era”, the event was described as “the first national convention of an underground movement that had existed on a hush-hush cell-by-cell basis,” according to countercultural chronicler Tom Wolfe. Sets from the Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company galvanized the audience, but the avant garde Tape Music Center was also on the bill.

In ‘80s and ‘90s, a new generation of counterculture congregated at San Francisco’s Baker Beach. Anarchists, artists and fringe-types gathered there for “fire” parties from 1986 to 1991 - the first iterations of Burning Man. When the Golden Gate National Recreation Area police forced the burn off the beach, the Wicked crew took its place. Fresh off the 1989 “second summer of love” in London when rave culture exploded, this collective of acid house DJs naturally chose the Bay as the locale to make a cultural musical mark in the states. Their full moon parties on Baker Beach became legendary. According to Wicked member Jeno, in the wake of the AIDS epidemic and its destructive impact on the Bay’s dance/disco scene, these parties, “helped define a dramatic change in SF's dance music culture.”

Along with San Francisco-based psytrance collectives like Blue Room and CCC, Wicked brought the rave to Burning Man, which had since moved to a lake bed in Nevada. Although at first relegated to the “techno camp” flung far from the center of Black Rock City, by 1996 electronic music was blasting from multiple “sound camps” on the playa. CCC, which lived in a warehouse on Howard Street in San Francisco’s SoMa (South of Market) neighborhood, would later found the Howard Street Fair, now the municipally-sanctioned How Weird Street Faire approaching its third decade of existence. (Similarly, Trips Festival promoter Bill Graham went on to purchase San Francisco’s 8,500-capacity Civic Auditorium, embedding counter culture into San Francisco’s municipal infrastructure).

Bay Area resident Andrei Olenev observed these developments, participating in them when age restrictions permitted him to. Andrei’s father was a visual artist in the psychedelic scene. (“Whenever you see a lot of good visionary artists on an event,” Andrei says, “it’s always a good sign.”) His father and older sister frequented Blue Room and CCC psytrance parties in the 1990s where attendees could cycle between rooms of different music like psy trance, jungle and chillout. Andrei would later produce music himself, a well-bred and barely terrestrial mix of dub, glitch, and drum and bass, first as Heyoka and today as Andreilien. On December 29, he’ll help open the ceremonies at Coalesce. “The styles of music changed,” says Andrei, “but that psytrance made a major contribution to the psychedelic electronic scene and festival culture.”

Andre Olenev performing as Heyoka at Symbiosis Gathering in 2009. (Credit: Dave Vann)

At the turn of the millennium, fresh sounds were diffusing throughout northern California and indeed the world. “I used to stay up late and record MTV AMP,” Andrei says, referring to the music video series that showcased tripped out work from Aphex Twin, The Orb, and Future Sound of London. Given the regions receptivity to psychedelic sound, these breakbeat and IDM (“intelligent dance music”) styles, like many more to come, hit in the Bay before they caught on elsewhere.

“In northern California in the early and mid 2000s there was constantly things going on,” Andrei recalls. “There was a very tight knit festival scene in northern California. I didn’t even know that much about southern California’s scene.” Musical trends found were given fresh interpretations in the region’s open and innovate environment. “There was a wave of IDM all over the place,” he notes. “A lot of IDM I heard from other places was a more experimental, more heady listening music. The California version was just a little bit more dance-oriented, more fat and bass heavy.”

On the beaches stretching from Santa Cruz to Half Moon Bay south of San Francisco, this music and culture thrived. During the 1990s the Wicked crew illuminated the sands with billowing bonfires and screeching acid house. During the mid 2000s broken beats began rumbling out over the waves at DIY parties thrown by crews like Rain Dance, led by “Little” John Edmonds. This collective has been booking bass music in the region for over two decades at annual urban events like Freakers Ball (Halloween) and Chinese New Years or at its Rain Dance Campout which began in 2002 in the woods east of Santa Cruz, “one of the few remaining underground campouts from that era that’s still going on,” according to Andrei. (Rain Dance may have been the first crew to book Tipper within the United States).

Rodman “Lux” Williams performing at a Santa Cruz hideout known as Toxic Beach in 2006. “My older friends who are in the scene definitely thought of him as a pretty legendary underground dude,” says Benji Hannus, a partner with Oakland-based promoter Wormhole Music Group. “Never released a whole lot of music, but played all the parties and was super well respected.” (Credit: Kyle Hailey)

Producers like Si Begg and southern California native SOTEG aka Bil Bless began to innovate on breakbeats. “From what I heard,” says Andrei, “some guys would take breakbeat records that were 45 and play them on 33, and that whole sort of sound evolved.” Building on these early innovators, Santa Cruz regulars like DJ Lorin (soon to become Bassnectar) and Rodman “Lux” Williams began to dominate dances with deep, heavy blends of breakbeat and glitch music. “Then Edit and Ooah [later of The Glitch Mob] started coming up from Los Angeles,” Andrei remembers, “and they had that super glitchy sound. Edit was definitely influential in all of that.” Andreilien rapidly gained traction in this scene when he began performing in 2007.

Back in The City, lineups thick with glitch hop began appearing at underground warehouses and above ground clubs. One more mainstream nexus was the club 1015 Folsom, where talent buyer Adam Ohana (An Ten Nae, Dimond Saints) booked huge glitch hop parties and “after burns” where artists like Freq Nasty would headline above Tipper, with DJ Lorin on the undercard. Farther off the beaten path the Cell Space warehouse hosted Rain Dance yoga parties, and from 2004 to 2006 a prolific gathering called Synergenisis where downtempo glitch producers like Bluetech performed and visionary art was spotlighted, including the work of Alex and Allyson Grey. Grittier fare could be found at warehouses like the Cracktory where UK dubstep producers like Distance made some of their first stateside appearances. Each venue contributed to a germinating scene and offered spaces for a new generation to join the party.

Benji Hannus is a partner with Wormhole Music Group, an Oakland-based music label and the crew behind the East Bay’s popular bass music weekly Wormhole Wednesday. Wormhole is working closely with Cosmic Synergy to promote Coalesce and to kick off the weekend with a bonkers pre-party at their home venue, The New Parish in Oakland. Benji, who produces cinematic psychedelic bass music as Secret Recipe, grew up in Berkeley and but for one year of college in Colorado, he’s lived in the Bay his whole life.

Benji traces his fascination with electronic music and event production to the night of his high school graduation in 2009 when he and some pals saw Shpongle at a festival in Santa Rosa. They found some flyers for Symbiosis Gathering, happening later that summer in Yosemite Valley. “If you know anything about Symbiosis,” Benji tells me, “especially that year, it was a pretty pivotal event for the west coast bass music scene, and for the underground electronic festival scene in general.” (The Symbiosis Gathering was held on the same grounds as early Rain Dance Campouts, symbolizing how the festival in some ways sprang from the early Santa Cruz scene). Headliners at Symbiosis ‘09 included Shpongle, Digital Mystikz, Bassnectar, Edit and Ooah, who combined their solo projects to perform a rare “Crying Over Porcelain for No Reason” set, and Amon Tobin, who will perform his own rare side project Two Fingers at Coalesce. The lineup rode the tail end of the glitch hop wave, and the rising tide of dubstep.

Upon returning from a year of school in Colorado, Benji moved to Santa Cruz and started his own event production company Forever Endeavor. “There was a very large renegade scene in the mountains. We’d bring a generator and some speakers out to the woods and have a free, illegal party.” The distinction between legal, permitted parties and illegal warehouse/outdoor parties is critical in California. In recent years, the DIY scene has nosedived. While some of its spirit and music moved above ground, as much if not more moved out of town. “At that time,” says Benji, “there’d be renegades with G Jones, when he still went by Grizzly J or Minnesota headlining way before he blew up. Many artists that have gone on to big things were based there at the time going to school at UC Santa Cruz.”

Tipper performing in 2009. According to Benji Hannus of Wormhole Music Group, Tipper performed unannounced at Rain Dance Campout in 2010. “He just showed up at the gate, said hi to all his friends, and played a Sunday set.” (Credit: Kyle Hailey)

“When I turned 21,” Benji recalls, “and could finally go to all the parties in SF in 2012, I would go to the city like 5 or 6 nights a week.” Every night there were weekly parties like Ritual Thursdays, a dubstep night, or Beat Church, a glitch-oriented evening that helped Heyoka get his start. On the weekends, huge four-room bass music parties raged at 1015 Folsom. It was this year that partners Morgan McCloud and Gleb Tchertkov founded Wormhole and began hosting Wormhole Wednesdays. The weekly bounced between different venues before settling into an Oakland club called Era. Benji, who had production chops and a modest roledex of agents and artists from his time in Santa Cruz, soon joined Wormhole full time.

Meanwhile, currents began to churn that would change the cultural and economic topography of the Bay and impact the underground bass music scene as a result. The Bay Area recovered more rapidly than most regions after the severe economic downturn of 2008. By 2015, eight of California 12 counties with unemployment rates below the national average were in the nine-county Bay Area region, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. Credit went to the rising tech sector, which engendered a thriving white collar economy.

San Francisco is already a small city, with a population under 900,000 a land mass of 46 square miles (New York City is over 300 square miles by comparison). Housing always had a degree of desirability and exclusivity, then the tech boom brought on an unprecedented influx of affluence. By 2015, as the producer of documentary San Francisco 2.0 Alexandra Pelosi put it in The Daily Beast, “not a week goes by without a headline about the growing pains brought on by the tech Gold Rush in San Francisco.” The struggle over “who gets to live in The City” escalated.

Soaring rents dramatically impacted poor and working class neighborhoods in San Francisco and Oakland, as indeed they did across America. In the Bay, though, the neighborhoods were generally filled with a higher percentage of artists and musicians. Warehouses that skirted the line between work spaces, living quarters, and venues - “empty” from a municipal and tax standpoint - were low hanging fruit for developers. “Otherworld was a huge staple for underground parties in the Bay for about 15 years,” notes Benji. This warehouse, where Wormhole hosted one of its larger un-permitted parties, was razed by developers in 2016 and replaced by luxury condominiums.

The East Bay fared better than San Francisco, though, and Wormhole Wednesday tapped into this dynamic when they began to push their weekly party. “We never really thought we’d get anywhere near as many people out as we did for a venue bass music party in Oakland, let alone on a Wednesday,” Benji says. “We pretty quickly discovered just how many people moved out of San Francisco and into the East Bay because it’s [SF] so unaffordable.”

Technology was not the only fluctuating economy that impacted the underground electronic scene. “When I was a teenager going to festivals,” Andrei recalls with a chuckle, “pretty much every person at the festival was involved in the weed business in one way or another. People would come from all over the world to go to Burning Man and then go to the hills in California and trim for a couple months.” Cannabis workers and their non-traditional hours filled electronic dance floors in the Bay and helped sustain weekly bass music parties. As the black market for marijuana has shrunk over the last decade, there’s less money in California cannabis. Some of that money - and some of the bass music, for that matter - has moved to Denver.

The Ghost Ship warehouse space from above on the morning of December 3, 2016, after a fire broke out which would claim 36 lives at an unpermitted party.

The psychedelic electronic wave in the Bay Area had crested, then, and assumed a slight downward trajectory by the mid 2010s. On December 2, 2016, the bottom fell out entirely. That night, California’s then deadliest fire since the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 claimed 36 lives during an unpermitted party at the Ghost Ship, a prominent Oakland warehouse and artist loft. DJs, promoters, artists and fans integral to the region’s broader arts scene lost their lives. It’s hard to overstate the impact this had worldwide and in the Bay. Prominent warehouses in Oakland and indeed across the United States either were shuttered or went on hiatus. Evictions ran across Oakland.

“We had an underground event at my friends’ warehouse scheduled for the week after,” Benji told me. “It was in a much safer space, but we decided to cancel it and eat a bunch of money. That hit our community pretty hard here.”

Notwithstanding the Ghost Ship tragedy, the psychedelic electronic scene in the Bay Area is in some ways a victim of its own success. “The type of music Coalesce is centered around,” Benji observes, “the more psychedelic side of things, and glitch hop specifically, that’s what’s really declined in popularity here. I think much of that involves the fact that a lot of that music came out of the Bay Area in the first place. People get burnt out on stuff and tastes change.” Ultimately, though, its not about the music. Music is just the strongest magnet to attract like-minded individuals and their energy,

Although it’s not like the area is some barren cultural wasteland. Nor is it void of individuals still dedicated to the sound and movement. It’s still the San Francisco Bay, after all, and it's psychedelic nervous system seems due for a shot in the arm. “As for the scene I know out here,” Andrei asserts, “there’s always a lot of old schoolers helping to guide the whole thing, who are still helping to run the festivals, or stage managing, or keeping the underground flame alive, you know?”

These multiple generations are set collide on New Years Eve. As was the case half a century earlier, creators, vibrators, musicians, oddballs, artists and visionaries will coalesce along the Bay’s misty shores to partake in a new medium of communication and entertainment.

FOLLOW Coalesce: Event / Tickets / Pre Party / After Party